Who’s more brilliant—men or women? Although this question is crass and usually not asked explicitly, questions like this often operate behind the scenes in people’s minds. The answer to such a question may have serious consequences for people in the real world. If an employer is evaluating two equally qualified candidates—one male and one female—that employer is likely to rely on his or her beliefs about men and women when making a decision on who to hire.

A few years ago, I and a few of my colleagues at the University of Illinois and Princeton University started to look into whether a stereotype exists that associates intellectual giftedness with men more than with women. Specifically, we looked at the language that college students use to describe their professors on the popular teacher evaluation website www.RateMyProfessors.com.

What we found was striking: In every academic field, students described their male professors with terms such as “brilliant” and “genius” more often than their female professors—even in fields with more female professors! At the same time, students didn’t differ in their use of the words “excellent” and “amazing” when describing male and female professors. According to students, male and female professors are equally effective in their teaching—but the male professors are more likely to be brilliant.

In light of these findings, we decided to examine this “brilliance = men” stereotype more directly. We wanted to confirm that the stereotype exists and, if so, to understand how pervasive that stereotype might be.

A challenge in researching stereotypes is that people are generally not willing to admit that they hold negative stereotypes and, in fact, may not even be aware that they do so. As a result, we used a task that didn’t require research participants to answer any questions at all. In fact, all they have to do is sort!

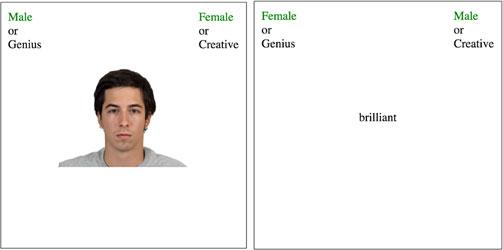

In this “Implicit Association Test” (or IAT, which you can take yourself at https://implicit.harvard.edu), participants were presented with images or words on a computer screen that related to one of four categories: male, female, genius, or some comparison trait (such as creative, friendly, or funny, depending on the study). When an item from one of these four categories popped up on a participant’s screen, the participant simply had to sort that item into its appropriate category (to the left or right) by pressing keys on the keyboard.

The image above shows two example trials of this task. In both cases, the participant would need to sort the presented item—either the photo of the man or the word “brilliant”— to the left because the image of the face fits into the category “Male” and the word brilliant fits into the category “Genius,” and both of these categories are located on the left side of the screen for these trials.

Notice which categories are paired together in the two trials. On the left example, “Male” and “Genius” are both on the same side. On the right example, “Female” and “Genius” are instead together. These pairings are important. The idea behind the task is that, if a bias exists in favor of men’s intelligence, the trial on the left will be much easier than the trial on the right. That is, if a person believes that men are more intellectually gifted than women, sorting the “genius” words with the male faces will be easier than sorting the “genius” words with the female faces.

By measuring how long it takes for participants to sort each item and by tracking how many mistakes participants make, we can pick up on participants’ gender biases without actually explicitly asking them anything!

We used different variations of this task in a variety of different groups of participants. In one study, we recruited adults from across the United States online. In another study, we recruited college students from the University of Illinois and New York University. We then tried this task on 9- and 10-year-old children, and we conducted an international study with adults from 78 countries in seven geographic regions of the world: Eastern and Southeastern Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, Northern and Sub-Saharan Africa, Southern Asia, Western Asia, and Western Europe.

In all of these studies—for adults and children in the United States, college students, and adults internationally—we found that people consistently tended to associate “brilliance” and “genius” more with men than with women. These results point to a pervasive and insidious stereotype against women’s intellectual abilities and in favor of men’s.

These disheartening results may have implications for women’s representation in higher education (especially in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields that are often said to require intellectual giftedness), career prospects, and more. Additional research is needed to understand the sources of these stereotypes about intelligence and their implications for men and women alike.

For Further Reading

Storage, D., Charlesworth, T., Banaji, M., Leslie, S. J., & Cimpian, A. (2020). Adults and Children Implicitly Associate Brilliance with Men More Than Women. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 90, 104020.

Storage, D., Horne, Z., Cimpian, A., & Leslie, S. J. (2016). The Frequency of “Brilliant” and “Genius” in Teaching Evaluations Predicts the Representation of Women and African Americans across Fields. PLOS ONE 11(3): e0150194. Available at https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150194

Leslie, S. J., Cimpian, A., Meyer, M., & Freeland, E. (2015). Expectations of brilliance underlie gender distributions across academic disciplines. Science, 347(6219), 262–265.

Bian, L., Leslie, S. J., & Cimpian, A. (2017). Gender stereotypes about intellectual ability emerge early and influence children's interests. Science, 355(6323), 389–391.

Daniel Storage is a professor at the University of Denver. His research program focuses on the causes of underrepresentation of both women and racial/ethnic minority groups, particularly in higher education.