In this piece, we are continuing from last month's recap of the SPSP 2023 Presidential Plenary on Social Norms, with talks from Drs. Guy Elcheroth and Cristina Bicchieri. Read on for the recaps and check out Part 1 here!

How Norms Change Faster: Social Creativity in Times of Crisis – Guy Elcheroth, University of Lausanne

A large part of the study of human behavior focuses on change, from perceptions and beliefs to norms and behavior. In his talk, Dr. Elcheroth offers a perspective that change during challenges contexts is different from the change that occurs during times of relative peace. Difficult times (think world wars, pandemics, etc.) herald rapid changes in the daily lives and behaviors of people. These disruptions often occur at a pace and scale with which people are often radically unfamiliar and can be difficult to understand. It seems that the most consequential changes are the hardest to comprehend or predict.

Common-sense intuitions cannot always help us in the case of non-linear, rapid change, such as when the pace of previous change is different from the pace of future change. Once a feedback loop is established in this case, the relative importance of the root cause of the change diminishes. However, traditional research methods used to study change, like regressions and assumptions of stable relationships between predictor and outcome, are built on such assumptions. This has led to social psychological research studying popular uprisings from a point of view removed from the people at the center of it. They are instead rooted in researchers' own positions and ideologies, leading to suppositions that collective situations can escalate rapidly and contagiously, leading to a breakdown of values and humanity. However, modern research on collective behaviors disputes this conclusion.

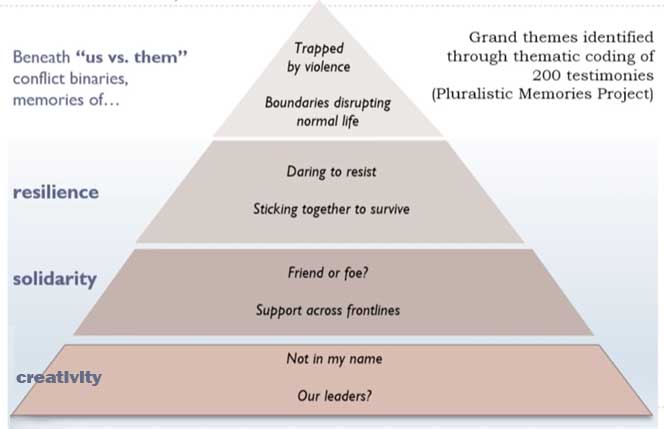

Dr. Elcheroth chairs the The Pluralistic Memories Project, which studies collective memories in conflict zones in order to understand how communities can remain resilient to the exploitation of past trauma. Studying three communities that endured political violence (Sri Lanka, Berundi, and Palestine), researchers found evidence of stories testifying to the resilience, creativity, and solidarity of communities amidst crises (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. Themes identified through coding 200 testimonies (Pluralistic Memories Project)

Perceived social norms can act as vehicles of rapid social change, the type that will be essential for combatting adverse climate change and global ecological breakdown. In a meta-analysis of social norm interventions for environmental conservation, researchers found that people systematically use less energy and material resources after learning that such behavior is normative. Similarly, public support for social distancing rules in the UK increased faster after the government imposed a strict lockdown. These examples suggest that perceived norms may act as a catalyst for rapid social change for the greater good.

How might perceived norms shift collective action behaviors in conflict settings? In a study conducted with Palestinians in the West Bank and Jerusalem, Dr. Elcheroth and colleagues found that the closer communities lived to Israeli military infrastructure and surveillance (e.g. the separation wall, checkpoints, or military barracks), the less likely they were to support cooperative forms of collective action (e.g. negotiations), although support for confrontational forms of collective action was unchanged (e.g. boycott). Could this impact of surveillance on collective action be explained by communication norms at the community level? Yes—participants' perceptions of the extent to which complex, alternative narratives of the conflict fit with local communication norms mediated the relationship between proximity to military infrastructure and the kind of collective action they supported.

These findings show that shifting social norms have the potential to accelerate social change because they orient behavior when stakes are high and values uncertain. They also have a self-reinforcing capacity and are sensitive to cues from public policy. In order to understand them better, we must be innovative in our research by employing multilevel study designs, non-linear modeling tools, and pursuing transdisciplinary collaborations.

Norm Dynamics – Cristina Bicchieri, University of Pennsylvania

How do we use "norm nudging" to change behaviors? Norms are supported by empirical expectations (what we expect others to do), normative expectations (what we expect others to approve/disapprove of), and conditional preferences. Norm nudging uses social information to induce change, under the assumption that the social information will change social expectations, thus fueling behavior change. However, there are mixed results for this method, where effects are often short-lived and sometimes fail altogether.

One of the reasons for the failures in norm nudging is the asymmetry of inferences that people draw from the social information they are given. However, not much attention has been paid to this factor and therefore we know little about how people draw inferences from social information. We know that people draw inferences about individuals (e.g. beliefs, attitudes) from social information about individual people—called social inference. However, making norm inferences about an overall group based on social information about a few people is difficult.

Dr. Bicchieri and PhD student Jinyi Kuang examined inferences that participants drew when presented empirical or normative information about 23 different behaviors. Dr. Bicchieri and Kuang found that for positive behaviors like driving below the speed limit, people made stronger normative inferences from empirical information. If participants are told most people pay taxes on time, for example, they infer that most people think it is right to do so. However, this is not the case when making empirical inferences from normative information. For instance if participants are told most people think it is right to pay taxes on time, they do not infer that most people do. This double asymmetry effect was flipped for negative behaviors like bribing public officers.

For some of the 23 behaviors examined, Dr. Bicchieri and Kuang found a double asymmetry effect. Others demonstrated only positive behavior asymmetry, while the rest showed no asymmetry. Possible explanations for the asymmetry outliers could be baseline expectations, frequency of the behavior, observability of behaviors, and social consequences (both objective and perceived). For behaviors having strong social benefit, there is a tendency to infer strong approval from empirical information and weaker prevalence from normative information (asymmetry). On the other hand, for behaviors with low positive social benefit, the inferences from empirical and normative information did not significantly differ (no asymmetry). In other words, when a behavior has low social consequences, participants believe that the prosocial behaviors of others are a genuine reflection of normative attitudes.

Taken together, to launch successful norm nudging efforts, researchers and practitioners must consider the characteristics of the behavior, perceived social consequences of the behavior, and assess the kind of norm inferences that will be drawn from information about the behavior, before designing messages that influence said behavior.

We thank Drs. Elcheroth and Bicchieri for sharing their findings and insights with convention attendees!