Aesthetic experiences can be powerful, even transformative. People find artwork moving or a sunset beautiful. And aesthetics is big business: everything from your social media feed to your coffee maker has been tweaked to appeal to aesthetic sensibilities. But how much can we really predict what people like?

Predicting Aesthetic Appeal

In recent years, several groups have applied powerful machine-learning techniques to predict what people find aesthetically pleasing. They've designed programs that can receive an image, identify a bunch of its features, and then guess whether people will find it appealing based on the sorts of images people have found appealing in the past. The features that matter include everything from how symmetrical the image is to whether it contains recognizable content.

But there is a limit to this approach because different people like different things. In fact, when we explicitly measure "shared taste," we find that people generally agree about the aesthetic appeal of faces and natural landscapes—things that exist in nature. But when people make aesthetic judgments of buildings or artwork—cultural objects made by people—we find that "shared taste" doesn't account for much of the variability in those judgments.

When Artwork Reflects Your Sense of Self

We were looking for a way to understand these idiosyncrasies, and we thought people might have radically different evaluations of artwork simply because they've led radically different lives. When you look at an artwork, you bring your own unique identity, memories, and beliefs to the table. Perhaps people find artwork more appealing when it relates to aspects of their sense of self.

To see if this was true, we asked people to rate real artworks for their aesthetic appeal and then rate them again for how much they related to them, their experiences, and their identities—how "self-relevant" they were. We found that the more a painting reflected the observer's lived experience, the more moved they were by it. In fact, self-relevance was a strong indicator of aesthetic appreciation even beyond people's familiarity with the work or any of the features we could derive from the images themselves.

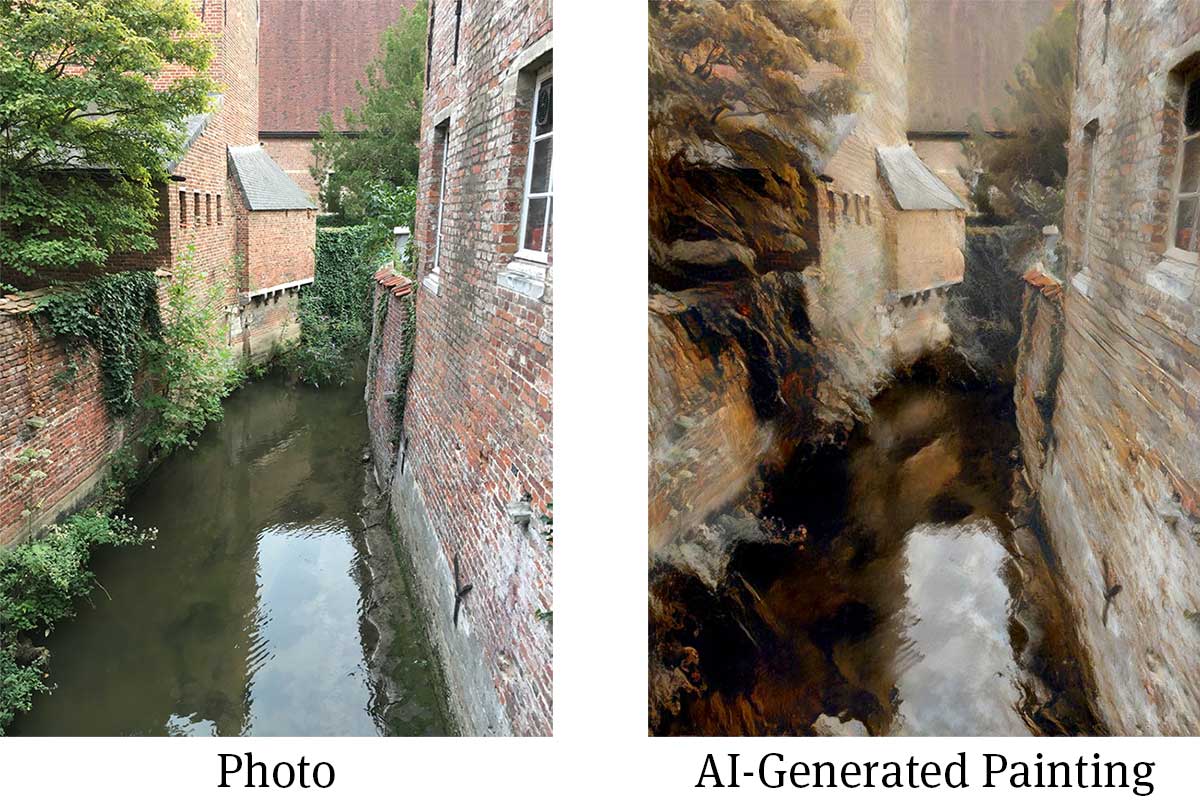

In a second experiment, we went a step further, creating customized artwork for each participant. We found images they would relate to, based on the personal memories and identities they reported in an initial survey. Then we used an artificial intelligence algorithm to apply the style of existing artworks to the photographs, turning them into "paintings."

See the images below for an example of a photo that might be relevant to a person's recent travel memories and what it would look like as an artwork.

A few weeks later, we asked participants to rate the aesthetic appeal of artworks we designed for them, artworks designed for somebody else, and a set of real artworks. Once again, self-relevance had a big impact. People consistently gave higher aesthetic ratings for images that we had tailored to them.

Why Do People Like Art That Relates to Them?

Why does this happen? We think it's because aesthetic appeal is strongly linked to our ability to create meaning. It is a form of "pleasure from understanding." When something relates to our own sense of self, which sits at the core of our structured knowledge of the world, we can get more meaning from it, and this gives us more pleasure.

Of course, people don't always use art as a "mirror" on themselves. Art can also be a window into the experience of others. But when a person can relate an artwork to their own experience, this acts as a map, allowing them to go deeper and unlock additional layers of meaning. Ultimately, this helps increase our understanding of the experiences of others.

To my relief, we also found that people generally liked real artwork more than AI-generated artwork. Artists, with their skill, their experience, and their artistic intent, create works that can capture something we weren't able to mimic. But by making AI-generated content specific for each person, we could uncover a critical ingredient of aesthetic magic: people liked the self-relevant AI-generated images more than the untailored AI-generated images, and they like them just as much as real art.

Toward a Psychology of Aesthetic Appreciation

Why is any of this important? First, it helps us understand why two people can look at the same thing but have different aesthetic experiences. This is particularly true for our experiences of things made by humans. After all, isn't a breathtaking natural landscape relevant to everyone?

It also highlights a pressing social issue. Many media companies build their businesses on creating individual models of consumers and serving them personalized content. With recent advances in AI and data science, it has become trivially easy to create highly stylized, personally relevant content. We hope our work can spark a conversation about the potential benefits, but also the potential downsides of personalized art. Because this kind of tailored content can be rewarding and addictive, we need to think about smart policy proposals to guard against abuse.

For Further Reading

Vessel, E.A., Pasqualette, L., Uran, C., Koldehoff, S., Vinck, M. (2023). Self-relevance predicts the aesthetic appeal of real and synthetic artworks generated via neural style transfer. Psychological Science. DOI: 10.1177/09567976231188107

Iigaya, K., Yi, S., Wahle, I. A., Tanwisuth, K., & O'Doherty, J. P. (2021). Aesthetic preference for art can be predicted from a mixture of low- and high-level visual features. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(6), 743–755. DOI: 10.1038/s41562-021-01124-6

Vessel, E. A., Maurer, N., Denker, A. H., & Starr, G. G. (2018). Stronger shared taste for natural aesthetic domains than for artifacts of human culture. Cognition, 179(June), 121–131. DOI: 10.1016/j.cognition.2018.06.009

Edward Vessel is a cognitive neuroscientist whose work focuses on aesthetics, creativity, and curiosity. Dr. Vessel recently completed a research stint at the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, and is now an Assistant Professor at the City College of New York, in New York City.