It's hard to talk about emotions. Sometimes people talk about their and others' emotions in ways that do not fully reflect reality. These distortions can help people perceive a world that matches their social and political views.

Modern societies are divided. Most individuals are either Democrat or Republican, Tory or Labour, Conservative or Liberal. A slew of research in the social sciences has showcased how people's strong emotional attachments to political groups result in social tensions between them. That is, people feel very positively about the party they support, and very negatively about the opposing party.

This polarization can have negative consequences: people try to maximize the difference between themselves and those who support the other political party. For example, they hesitate to speak with opponents, don't want to live close to them, and avoid having them as co-workers. They even shorten their Thanksgiving dinners if that lets them minimize time with opposing family members.

People can also distance themselves from political opponents by how they talk about emotions. Previous research suggests that some emotions, such as joy and worry, are socially desirable and others, such as anger and fear, are socially undesirable. I hypothesized that people ascribe desirable emotions to their own group and undesirable emotions to the opposing group and its supporters. For example, Democrats might say that the Democratic Party and its supporters are driven by love, joy, compassion, or worries about society's future. With these emotions, they elevate their own group and make it appear nice. Democrats might also say that the Republican Party and its supporters are motivated by anger, disgust, or shame. Such ascriptions devalue the opposing group.

Elevating one's own group and devaluing the other creates distance. "We love, they hate."

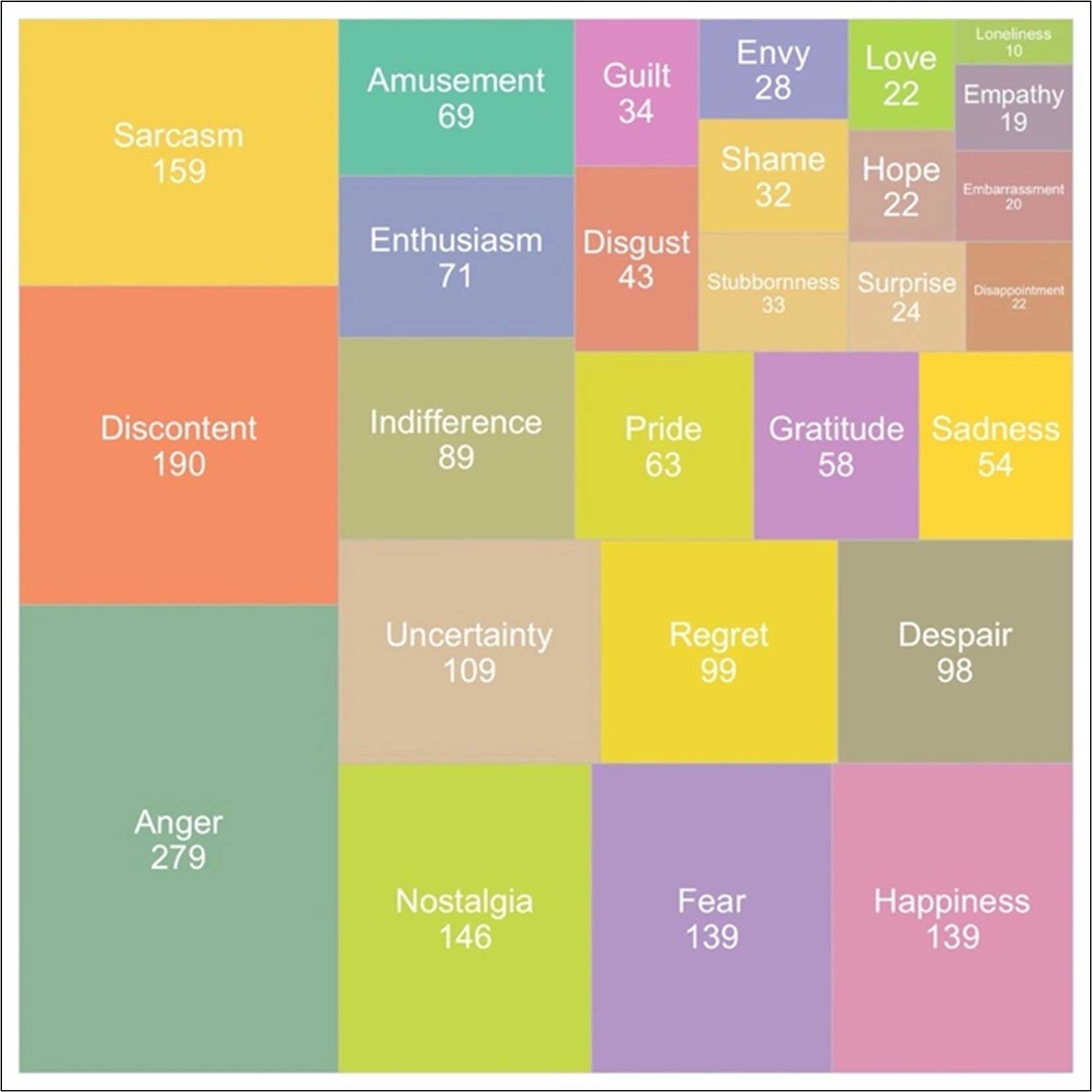

I developed and explored this theory by analyzing interviews with 27 German radical right voters. These were long conversations in which the interviewees talked about their perceptions of many different societal issues. I carefully went back through all the interviews, making details notes of the emotions people mentioned. I found that people mentioned a lot of emotions!

The image below summarizes all the emotions that came up in these interviews, including how often each one was mentioned.

Next, I analyzed how single emotions were used: Did respondents mention a specific emotion in relation to their own group or to the opposing group? I found that the interviewees tended to position their own group in a desirable light, displaying themselves as concerned but lenient, sometimes benevolently worried, and often joyful and proud. For instance, one interviewee seemed angry about what he considered an "exuberant, desire-based market economy." However, instead of voicing his anger about the opponent, he phrased it in a more socially desirable way: "I don't know if I expressed myself correctly, but that is something I don't understand about the ladies and gentlemen of the Green Party."

In contrast, the interviewees pictured opponents as apathetically indifferent or anxiously passive, often angry and sad. For example, one interviewee described opponents as anxious: "This is fear. This is fear, this is panicking, and many people don't want to get out of it. They don't want to leave their bubble."

So, these radical right-wing voters tended to suggest that their group experiences socially desirable emotions like pride, happiness, or worry, and that their opponents are motivated by undesirable emotions like anger, sadness, or indifference.

These data illustrate another political bias that was poorly understood before. In the political realm, these "emotion portrayals" may be an easy, cheap, and permanently accessible way for partisans to maintain and even further division.

To be sure, my interviews only considered the perspectives of one political group. I don't know if the same bias would emerge for other political groups—in Germany or in any other country. More studies like this will help clarify how common this bias is and whether it's responsible for strengthening political polarization.

But until then, it's worth being more careful in how you talk about your emotions. Are you conveying ideas about emotional experiences in a way that deepens or bridges political divides? One possible strategy is talking about shared emotions or appreciating the other group's genuine emotional concern. These simple practices could help you break free of the kinds of polarizing biases that may contribute to deep social divisions.

For Further Reading

Versteegen, P. L. (2024). We love, they hate: Emotions in affective polarization and how partisans may use them. Political Psychology. Early view. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12955

Bakker, B. N., Schumacher, G., & Rooduijn, M. (2021). Hot politics? Affective responses to political rhetoric. American Political Science Review, 115, 150–164. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000519

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22, 129-146. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

(Peter) Luca Versteegen is a PhD Candidate at the Political Science Department of the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. He studies how identities and emotions drive individuals' perceptions of and reactions to societal developments and how they motivate radical political behaviors like radical right support or affective polarization.