Critical race theory and "anti-racism" are hot-button topics you've likely seen mentioned in the media. Critical race theory (CRT for short) is a set of ideas developed by law scholars to illustrate how aspects of history, culture, and political institutions advantage certain racial groups to the detriment of others.

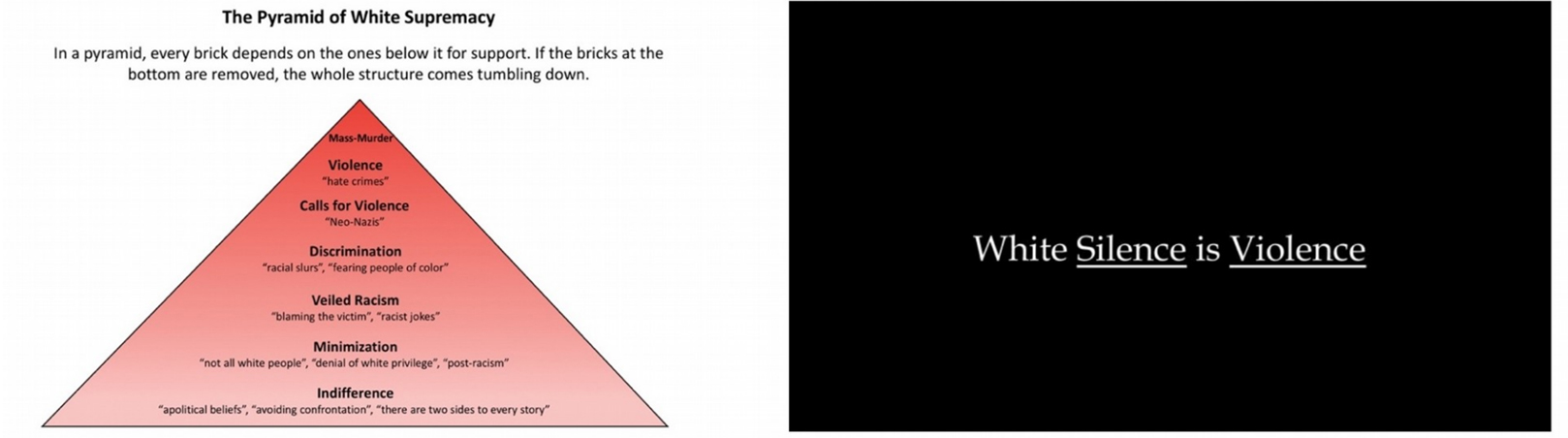

While some view CRT, anti-racism, and associated messages like "White silence is violence" and "The pyramid of White supremacy" (see below) as key to raising awareness and addressing the problem of racism, others view these messages as wrong, divisive, and harmful. Television outlets like Fox News warn about the peril of bringing such messages into the classroom, and several states have banned anti-racist messages (and CRT more broadly) from government organizations.

Our research team conducted several studies to answer the question: Why do the same messages about racism evoke such different reactions?

Examples of two anti-racist messages—“the Pyramid of White Supremacy” and “White Silence is Violence”

Examples of two anti-racist messages—“the Pyramid of White Supremacy” and “White Silence is Violence”White People Push Back When They Interpret Anti-Racist Messages to Say That Silence Is the Same as Violence

We suspected supporters and opponents of CRT messages might have different interpretations of these messages, and that these interpretations lead to more or less support.

Across several surveys, we showed White Americans messages like "White silence is violence" or "The pyramid of White supremacy," and then asked them to rate how much they agreed with statements like: "This message argues that people who are silent about race issues in America are themselves engaging in racial violence" and "This message argues that being silent about racial issues makes you a blatant racist." These statements reflect an "equalizing interpretation"—that the message directly equates silence about racial injustice with actual violence.

We also asked participants to rate statements like: "This message argues that being silent about racism creates a foundation which can lead to racial violence occurring in our society." These statements reflect a "building block interpretation"—that failing to challenge racism paves the way for racial injustice.

These interpretations were not mutually exclusive—people could have both an equalizing interpretation and a building block interpretation. But while the majority of people had a building-block interpretation, our respondents were almost split down the middle in whether they held an "equalizing interpretation"— believing that anti-racist messages portray silence as the same thing as blatant racism.

Interpretations mattered. We asked participants how threatened they felt by the anti-racist messages, how much they opposed them, and how motivated they felt by the message to engage in anti-racist action. Having an equalizing interpretation went hand-in-hand with feeling threatened by anti-racist messages, opposing these messages, and not feeling motivated by the message to engage in anti-racism. Having a building block interpretation was associated with the opposite.

What Are Anti-Racist Messages Really Trying to Say?

But what really is the core message of CRT and anti-racist messages? We suggest that CRT and anti-racist messages try to promote the building block interpretation we found to be associated with support for anti-racist messages.

CRT argues that to fight racism—to be anti-racist—it is important to not only combat the racism that individuals enact, but also, that which societies do, too.

When people think about racism, it is intuitive to think of "the racist individual"—the bigoted person behind the white hood. That is, people often think of racism as something that individuals are responsible for: something inherent to a person's behavior, attitudes, and character.

But racism has another side. Racism is also something that societies enact—biases that are rooted in shared history, reflected in policies and institutions, and that shape how power is distributed, and define what is good, bad, and normal.

If racism is something that manifests at a societal level, then it is not enough for people to "not be racist" themselves. It is important to also act against racism, by breaking the silence which functions as a building block for a racist society.

Racism can be combatted by critically assessing and challenging the policies (such as regulations for getting a mortgage), institutions (like the criminal justice system), and shared ideas of society (for example, what is shown as "beautiful" on TV) that advantage certain racial groups while disadvantaging others.

How Do We Decrease White People's Backlash to Anti-Racist Messages (And Is This Even the Right Question to Ask?)

What do our findings say about the utility of anti-racist messages for encouraging anti-racist action? Our findings suggest that interpretation matters: When White people interpret a message like "White silence is violence" to literally equate their silence with engaging in violence, they tend to push back. But when White people interpret that message to mean that silence is a key building block for racial violence, they tend to support the message and become motivated to engage in anti-racist action.

One solution then, to making anti-racist messages more effective in promoting anti-racist action, could be to modify their wording so that White people are less likely to push back. In some of our later studies, we found support for this idea: When we showed White people a message like "White silence is a foundation for violence," they reported less resistance and more anti-racist motivation than when shown the original "White silence is violence" message. Importantly, we also found that the modifications we made to anti-racist messages did not reduce how effective people felt the message was at communicating the harm of silence, relative to the original message.

But we also caution rushing to discard original anti-racist messages. These original messages are powerful because they capture people's attention and communicate the anger and pain of groups who have been disempowered by the racism in society. Members of marginalized groups have long felt threatened. Should their messages be changed even if they threaten some members of groups who have historically been advantaged? This is a question for people to reflect on and answer as a society. What will be important as people engage with challenging messages about racism is for them to take a step back and consider how their interpretations of these messages shape their reactions, and then make efforts to inquire about the intended meaning behind these messages.

For Further Reading

Kachanoff, F. J., Kteily, N., & Gray, K. (2022). Equating silence with violence: When White Americans feel threatened by anti-racist messages. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 102, 104348.

Ray, R., & Gibbons, A. (2021). Why are states banning critical race theory? https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2021/07/02/why-are-states-banning-critical-racetheory

Salter, P. S., Adams, G., & Perez, M. J. (2018). Racism in the structure of everyday worlds: A cultural-psychological perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27, 150- 155. Doi: 10.1177/0963721417724239

Frank Kachanoff is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at Wilfrid Laurier University. He studies how psychological processes related to culture and identity impact people's well-being, and (in)equity within our society.

Nour Kteily is a Professor of Management and Organizations in the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University. He uses the tools of social psychology to investigate how and why conflict emerges between groups in society, and how to equitably resolve it.

Kurt Gray is a Professor in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He uses interdisciplinary methods to study deeply held beliefs and how to bridge moral divides.