Studies show that 83% of released prisoners are rearrested within a decade. That rate of recidivism is obviously bad for society and for the individuals who are trapped in a cycle of bad decisions and awful consequences.

Beneath the very high rate of reoffending lies the hard reality of rejection that prisoners face upon release from prison. Ex-prisoners are often not allowed to vote, they struggle to find work, and people think they are dangerous and bad people, a belief that members of the public readily convey. In other words, ex-prisoners are rejected from the society they are trying to reenter. This rejection makes life after prison stressful and depressing, and stressed and unhappy ex-offenders often re-offend.

Why does being rejected by society have such a strong effect on former prisoners? A great deal of research shows that a person’s social world is a core determinant of his or her health and well-being. Being a member of a rejected social group negatively affects well‐being, making people feel that they do not fully belong to society. Social connectedness, on the other hand, greatly benefits well-being by making us feel socially valued and accepted. Can these social processes explain how rejection affects ex-prisoners' well-being? According to our research, the answer is “yes.”

My co-authors and I conducted a study in which we asked ex-prisoners in the United States to tell us about their post-prison social life. We recorded information on their experiences of rejection, self-concept, social connections to other people, and psychological well-being.

The people who participated in this study struggled under the ongoing stigma that comes with the label “ex-convict.” They characterized America as an unforgiving society that makes it very difficult for people like them to turn their lives around. Here’s what one ex-prisoner said:

Just because you’re an ex-prisoner doesn't mean what everyone says. We made a mistake, we shouldn't be continually shamed for it over and over. We did our time, now we should be given a chance.

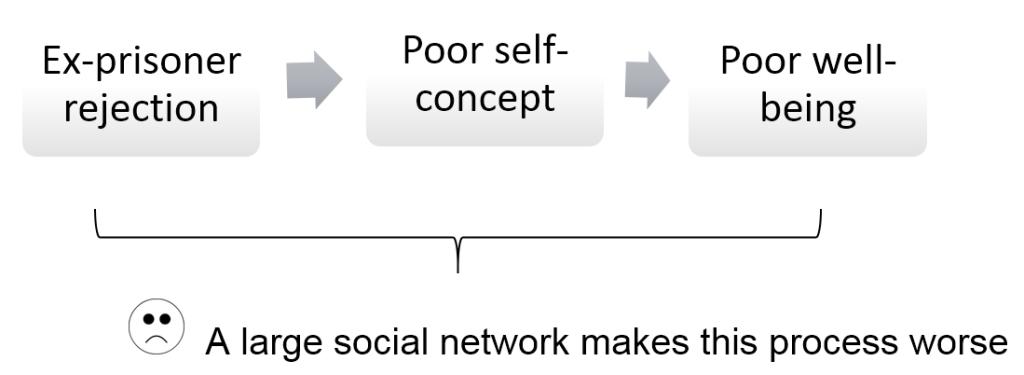

What’s more, the impact of this rejection on their well-being was due to its impact on their self-concept. In other words, being rejected made ex-prisoners feel bad about themselves. And, feeling bad about themselves led them to experience lower well-being overall.

You might think that one way to solve this problem would be to increase the number of social connections ex-prisoners have. Surprisingly, the opposite was true. We found that ex-prisoners with more social connections felt more rejected, and they consequently experienced lower well-being than those with fewer social connections. This was a surprising finding that seems contrary to almost everything that we know about the effects of social connections on well-being. Why would ex-prisoners with more social connections feel more rejected and experience lower well-being?

The answer seems to be that ex-prisoners who have larger social networks have more opportunities to be exposed to rejection for being an “ex-con.” Having more social connections means having more possible sources of rejection. In addition, having larger social networks makes it more difficult for ex-prisoners to manage their ex-prisoner self. Their identity as convicted criminals is incompatible with who they are trying to be in their new life.

Basically, ex-prisoners who are exposed to rejection develop a negative self-concept, which leads to poorer well-being. This process is more pronounced for ex-prisoners with larger social networks and more social connections. Here is the big picture:

These findings suggest that we need to rethink the way we treat ex-prisoners. New directions in resettlement strategies should help people to distance themselves from their criminal past and to prepare for the hard reality of rejection that they are likely to experience in their social network for being an ex-prisoner.

At this point, it’s too early to tell what implications our work has for recidivism. But, as our participants suggested, the way we treat ex-prisoners likely contributes to their likelihood to re-offend. This and other research questions – such as whether our findings generalize to other countries – are at the forefront of where we plan to take this research next.

What is clear from our research is that if we want to reduce crime and decrease the prison population, we need to find ways to allow people who have done their time to feel as if they are a part of society.

For Further Reading

Kyprianides, A., Easterbrook, M. J., Cruwys, T. (2019). “I changed and hid my old ways”: How social rejection and social identities shape well-being among ex-prisoners. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 49, 293-294. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12582

Branscombe, N. R., Schmitt, M. T., & Harvey, R. D. (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well‐being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 135–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.1.135

Haslam, C., Jetten, J., Cruwys, C., Dingle, G., Haslam, S.A. (2018). The New Psychology of Health: Unlocking the social cure. London: Routledge.

Arabella Kyprianides is a Research Fellow at UCL’s Department of Security and Crime Science. Her research is focused on the social determinants of well-being in the criminal justice context.

Matthew Easterbrook is a Lecturer in Psychology at The University of Sussex. His research focuses on the consequences of people's group memberships and social identities within different socio-cultural contexts.

Tegan Cruwys is a Researcher in the Research School of Psychology at The Australian National University and a practicing clinical psychologist. Her research investigates the social-psychological determinants of health, with a focus on health behaviours, mental health, and vulnerable populations.