In the classic Superman film starring Christopher Reeves, there was something strange about Reeves’ character’s hair. When he was in the bumbling Clark Kent character, his hair was parted on his right. But when he was in the powerful Superman character, his hair was parted on his left! Reversing his hair part every time he changed personas would have been logistically difficult for the film crew. So why do it?

It turns out that there is a widespread cultural belief circulating in fashion websites and magazines concerning how hair parts change a person’s looks. The general consensus seems to be that parting on one’s left makes a person look competent and masculine, whereas parting on the right makes a person look warm and feminine.

I learned about this while listening to one of my favorite podcasts, Radiolab (I’m a podcast junkie). The hosts put the notion to the test in front of a live audience by showing a classic picture of Abraham Lincoln and then left-right reversing the image to see if it looked different. The audience erupted into laughter as the co-host Robert Krulwich uttered disbelief, “Oh that… wait wait wait... No no no. Is that the same picture?... That’s so weird!”

I had a look for myself. Krulwich was right. Lincoln really did look different in the reversed image. But as a scientist, I wasn’t convinced that it was the hair part that made the difference. Sure, Lincoln’s hair part was reversed but so was his body position, his characteristic facial mark, the shadows on his face, and so on. Which of these features was making him look different wasn’t obvious to me.

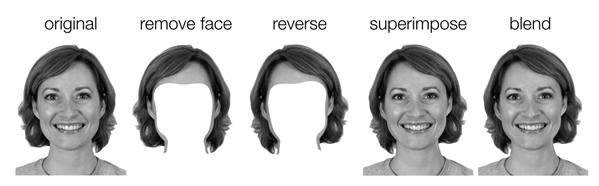

To get to the bottom of this, I figured that one would need to leave the face and body unchanged while reversing only the hair part. Using photo editing software, I did just this (see Figures 1 and 2). I then asked 800 Americans to look at the original and another 800, determined by random assignment, to look at the doctored image and judge how feminine, competent, warm, and attractive she looked.

Figure 1. The process that reversed the hair part without changing the face.

Figure 2. Portraits the participants judged.

The results were surprising. I found virtually identical and statistically indistinguishable appearance ratings for the photos with left-parted and right-parted hair. It didn’t matter if the subject was male or female, or had a neutral expression or was smiling. I then computed the odds that the location of the hair parts matter, and, statistically speaking, the odds that they don’t matter was 25 times more likely than the popular belief that hair parts do matter.

Viewing these results with healthy skepticism, I wondered if participants might have not been paying attention and that’s why I didn’t find any differences. But that explanation didn’t seem to pan out. Every other factor—whether the model was male versus female, had a neutral expression, or was smiling, and which trait was being rated—had a huge effect on ratings. Participants were paying attention alright. But whether the hair was parted on the left or the right didn’t seem to matter.

Another possible explanation for not finding a difference is that participants didn’t notice the person’s hair in the first place. To test this idea, I presented a new set of 900 Americans with both the left-part and the right-part versions of the female in Figure 2, side by side. Their task was to indicate which looks better: the left part, the right part, or there’s no difference. In spite of blatantly drawing participants’ attention to the way the hair was parted in the two images, the most common response was to indicate there was no difference (50% of responses). The remaining half was evenly split between choosing the right and left parts. These results lent even stronger support for the conclusion that, when it comes to appearance, hair parts matter not. The pop culture idea seems to be a myth.

Psychological scientists’ reactions to these findings have been as intriguing as the findings themselves. The biggest point of contention seems to be that the article that I published about this research offered no new psychological theory. After all, a theory is not needed to explain the absence of a thing. The journal editor who handled this article recognized this fact but still decided that putting widespread cultural beliefs to a rigorous test is a worthwhile objective.

Others saw it differently. An editor at another journal (hilariously) decided to not even send the paper out for review, writing “I personally find this research interesting and useful (my own hair parts naturally on the right and many barbers and stylists have unsuccessfully tried to change it to the left in efforts reminiscent of asking a left-handed child to write with his right hand)… Unfortunately, [this journal] puts a premium on the theoretical contribution of its published articles, and so I must regretfully inform you that we can’t move forward…”

I often wonder whether the primary goal of psychological research is to learn about the real world or whether the goal is to advance psychological theory. Some psychologists seem to be reluctant to test pop culture beliefs when the stakes for psychological theory are low. This reluctance may explain why, prior to my paper, the only definitive statement regarding hair parts coming from scientists was from a nuclear physicist and cultural anthropologist team (I’m not making this up), who claimed that hair parts matter and created a spin-off company selling non-reversing mirrors, which range in price from $225 to $1995. The methods and data presented in their article fell well short of current scientific standards. If it weren’t for a brave editor willing to publish an atheoretical null finding, psychology would remain reticent on a widely held false belief about psychology.

For Further Reading:

Frimer, J. A. (2019). Does the left hair part look better (or worse) than the right? Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10(3), 326-334. doi: 10.1177/1948550618762500

Jeremy Frimer is an Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of Winnipeg, Canada. His main area of research focuses on the weaponization of incivility in U.S. politics. This research on hair parts was a mental vacation from his primary research.