Sadists are the stuff of Netflix serial killer documentaries. People often imagine them as depraved monsters that exist at the fringes of society. But the truth is: sadists walk among us.

Sadism is the tendency to experience pleasure when inflicting pain on others. Although sadistic tendencies have been observed among the most heinous of serial killers, the tendency to enjoy others’ suffering exists in many people to one extent or another. We know this because personality questionnaires that measure sadism reveal that “everyday” people often report some degree of sadistic impulses. These measures of sadism ask people to rate how accurately statements such as “I have hurt people for my own enjoyment” and “I enjoy making jokes at the expense of others” describe them.

However, it is unknown whether such sadistic pleasure is fleeting or long-lived, and whether negative feelings may also come into play when people behave sadistically. It may be that sadists experience the pleasure of aggression only briefly and that, in the long term, these feelings are replaced by aversive emotions. To answer these questions, my collaborators and I decided to give participants with varying levels of sadistic tendencies the opportunity to harm other people and then see how they actually felt before, during, and after the act.

We conducted eight studies involving more than 2,000 research participants in which participants could harm someone using laboratory aggression tasks. For instance, in several studies, participants could select how loud and how long to play extremely harsh noise into the headphones of another person. In another study, they could pick how much hot sauce someone who hated spicy foods had to eat.

Across our studies, the more participants indicated that they had sadistic tendencies on personality questionnaires, the more aggressive they were toward other people. This relationship between sadism and aggression held even after taking other antisocial traits such as psychopathy, narcissism, and impulsivity into account. Interestingly, sadistic participants were often just as aggressive toward innocent victims as they were toward people who had insulted or rejected them. So, it doesn’t seem like sadists lash out just at those who wrong them. Instead, sadistic aggression is indiscriminate.

Supporting the idea that sadists really do enjoy hurting other people, sadistic participants reported that they felt more pleasure during these aggressive acts than non-sadistic participants did.

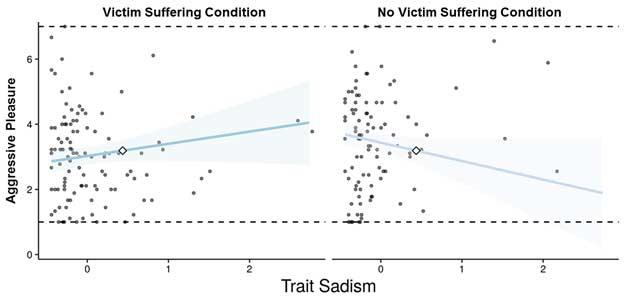

However, the sadistic pleasure experienced while being aggressive was not unconditional. In one study, we told half of our participants that their aggression actually hurt their victim (the noise blasts they administered caused the other person to have a painful migraine) or failed to actually hurt their victim (the noise blasts were just a little annoying). The graph below shows that sadists expressed more pleasure during the aggressive act only if they thought that their victim actually suffered. In fact, if sadists were told that their aggression had no harmful effect, they experienced less pleasure than non-sadistic participants did.

We also asked our participants how they felt soon after the aggressive act. Sadistic participants didn’t report any lingering afterglow from their hurtful behavior. Instead, they rated themselves higher on negative feelings such as sadness and anger. In other words, sadistic acts may have made sadists feel good in the moment, but they made them feel bad soon after.

Taking a bird’s eye view of these results, we see that people who say they are sadistic on questionnaires actually are. They’re aggressive and they enjoy their aggressive acts—as long as their victims feel the sting. This finding has some potential uses as it shows that a source of sadistic pleasure is the victim’s pain. So, one way to take the wind out of sadists’ sails may be to show them that their victims aren’t really suffering from their actions. Yet, this counter-intuitive approach needs further testing before it is used as anything close to a clinical treatment for sadism.

But we also see that sadistic pleasure is a flash in the pan and fades quickly. In its place is the bitter aftertaste of anger and sadness. In this way, sadistic aggression looks a lot like alcohol consumption, binge eating, or risky sex—it feels good in the moment, but the buzz fades and leaves behind a hangover that people are desperate to get rid of. Just as people who are alcohol-dependent may treat a hangover with another round of drinks, sadists might respond to the post-aggression doldrums by seeking another victim.

For Further Reading

Chester, D. S., DeWall, C. N., & Enjaian, B. (2019). Sadism and aggressive behavior: Inflicting pain to feel pleasure. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45, 1252-1268.

Buckels, E. E., Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2013). Behavioral confirmation of everyday sadism. Psychological science, 24, 2201-2209.

Chester, D. S. (2017). The role of positive affect in aggression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26, 366-370.

David S. Chester is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Virginia Commonwealth University. He studies the psychological and neurobiological forces that cause and constrain human aggression.