Right now, in North America, most people are single. Yet, very few of us wish to remain that way indefinitely. If given the choice, many of us would much rather be in a romantic relationship. Why? There are many reasons, but one reason is that, in a culture obsessed with romantic love, marriage, and general coupledom, being single has a bad rap. Singles are stigmatized with a host of negative traits including sad, insecure, selfish, and, above all, lonely. Indeed, the stigma around being single makes it seem like a dark and lonely existence. Despite the fact that these stereotypes do not reflect reality, they can be hurtful to people who are single. In that way, they are not unlike the kinds of negative attitudes documented towards other stigmatized groups.

This raises two important questions: Do singles feel alone in the face of stigma or do they feel like part of a larger social group of stigmatized individuals, and how do other people perceive singles as a group? Along with my supervisor, John Sakaluk, I conducted two studies to find out.

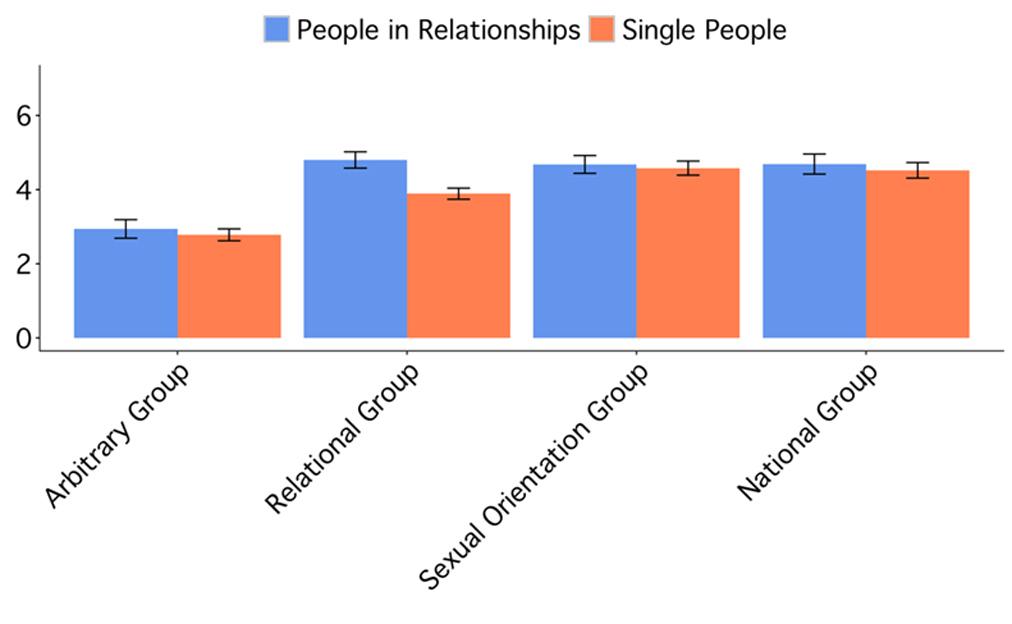

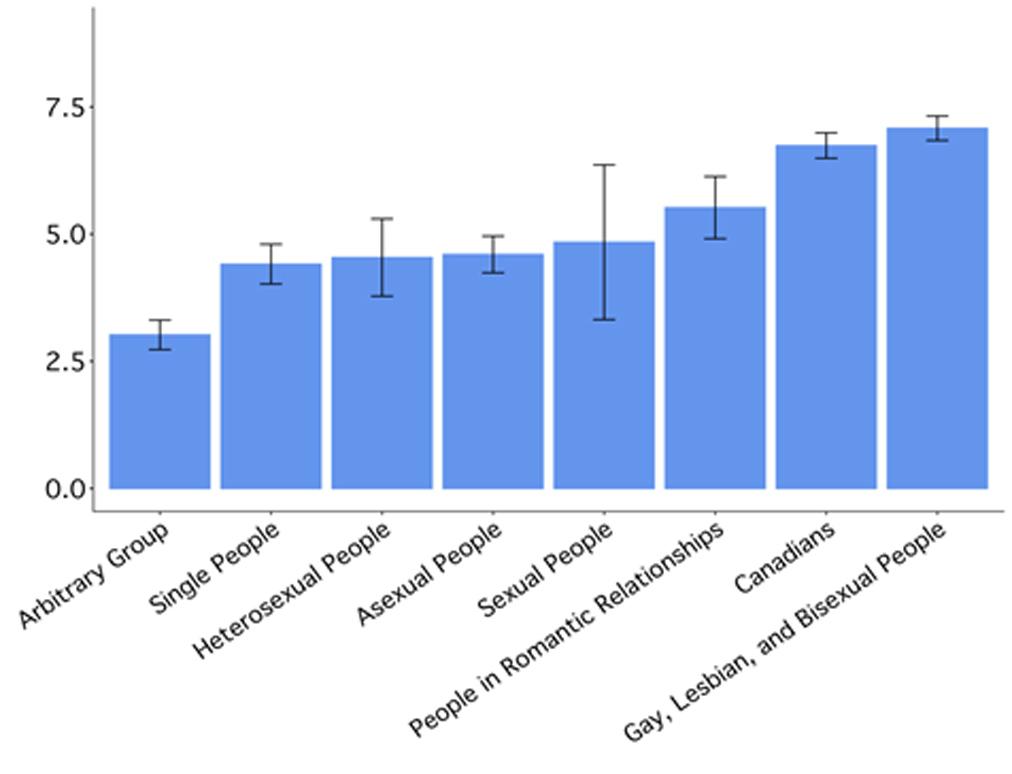

In our first experiment, we asked people how strongly they identify with three personal group memberships based on their relationship status, sexual orientation, and nationality, as well as with their membership in an arbitrary group to which they were randomly assigned. The purpose of this arbitrary group membership was to give people a new group membership that they wouldn’t feel a strong sense of identification with. Essentially, then, this arbitrary group assignment allowed us to establish a “low bar” of group identification against which we could compare people’s identification with their three personal group memberships, particularly single peoples’ identification with other singles. In our second experiment, we asked people to rate the ‘groupyness’ of five different types of groups, of which they were not a member, including singles and people randomly assigned to arbitrary groups. Basically, we asked people how much each group looks, acts, and interacts like a group.

So how did singles stack up compared to the most arbitrary—and most common—types of groups?

In both experiments, singles passed the lowest bar of “groupyness” as they self-identified as and were perceived by others as more “groupy” than people randomly assigned to arbitrary groups. These results, which are shown below in Figures 1 and 2, suggest that singles do pass a bare minimum threshold for being considered a bona fide social group. So, at least to some extent, singles do feel like they are part of a larger social group, and they are perceived that way by other people.

Yet, singles’ “groupyness,” as perceived by both themselves and other people, still fell short of other well-established groups such as those based on sexual orientation and nationality. This pattern suggests that single people may still have a ways to go before they are regarded seriously as a group, which could explain why people in our study were also more accepting of prejudice towards singles than toward other groups (see full article for more detail).

Singles also consistently self-identified and were perceived as less “groupy” than people in relationships, which could be another reason why marriage may be so attractive: Being married might provide people with a more culturally-valued and groupy identity compared to being single, which also comes with additional benefits for self-esteem and well-being. Therefore, greater efforts to increase the cultural value and groupyness of singles, such as through single-friendly policy and community initiatives, might improve singles’ lives as well as their sense of identification and pride in their single identity. However, more research is needed before we can know for sure.

Till then, we singles can rest assured that we are not alone—we are alone, together.

For Further Reading

Fisher, A.N., & Sakaluk, J.K. (2020). Are single people a stigmatized ‘group’? Evidence from examinations of social identity, entitativity, and perceived responsibility. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 82, 208-216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2019.103844

Day, M. V., Kay, A. C., Holmes, J. G., & Napier, J. L. (2011). System justification and the defense of committed relationship ideology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 291-306. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023197

DePaulo, B. M., & Morris, W. L. (2005). Singles in Society and in Science. Psychological Inquiry, 16(2-3), 57-83. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli162&3_01

Lickel, B., Hamilton, D. L., Uhles, A. N., Wieczorkowska, G., Lewis, A., & Sherman, S. J. (2000). Varieties of groups and the perception of group entitativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(2), 223-246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.223

Alexandra N. Fisher is a doctoral candidate in Social Psychology at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada. She studies self and identity in close relationships.