Many decades ago, the sociologist David Phillips conducted a series of studies suggesting that people have some control over the exact dates of their own deaths. For example, in one study Phillips and Kenneth Feldman examined the dates of death of 1,333 famous people. They found that people were less likely to die in the 6 months before their birth months than in the 6 months during or after their birth months, suggesting that they were postponing death until after their birthdays.

Because such a broad pattern is open to more than one interpretation, Phillips and his colleagues conducted additional research that focused on the exact days of people’s deaths. Among other things, they found that, in two large cities with large Jewish populations (New York City and Budapest, Hungary), death rates were higher just after than just before Yom Kippur (the Jewish Day of Atonement). Phillips referred to this tendency for people to avoid dying just before or during important holidays as a “death deferral effect.” Phillips and his colleagues replicated this finding both in a sample of California Jews and a sample of people in China who were likely to celebrate the Chinese Harvest Moon Festival.

Some social scientists expressed great skepticism about these findings. Can we really trust them? Do people really have any control over the exact dates of their own deaths? If so, what is the likely psychological mechanism behind this phenomenon? It is difficult to answer this last question. But we were able to answer the first set of questions (is the death deferral effect real?) and to begin to answer the intriguing question about likely mechanisms.

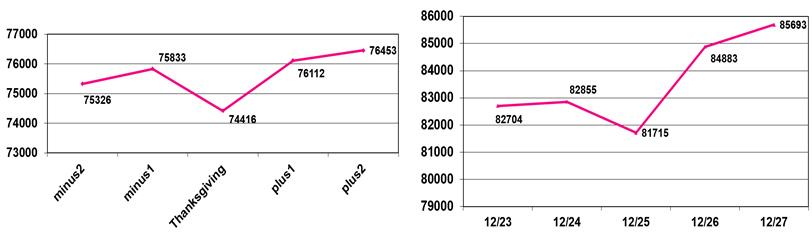

To see if there is a real, population-wide death deferral effect, we focused on the two most important U.S. holidays – Thanksgiving and Christmas. We used Social Security Death Index records to look at every death that took place in the United States between 1987 and 2002 (all of the dates for which exact dates of death were available) For both Thanksgiving and Christmas, we found that people did, in fact, defer their own deaths until just after the major holiday.

As you can see in the graphs below, for both Thanksgiving and Christmas, people were least likely to die on the actual day of the holiday itself and most likely to die two days after the holiday. It is particularly useful to have data for both Thanksgiving and Christmas because unlike Thanksgiving, which is always on a Thursday, Christmas comes on different days of the week in different years. Thus, the death deferral effect is not merely a day-of-the-week effect.

Our preferred interpretation of these findings is that people are so interested in experiencing each of these two major holidays that they somehow hold on to life until the holiday has passed. This could be due to changes in either their behavior or their psychological state. For example, when people know that death is around the corner, they often make choices about whether they continue to eat and drink enough to sustain themselves. The desire to be with loved ones may be enough of a motivator to get people to eat when they might otherwise allow themselves to waste away.

But is there any evidence that these death deferral effects are connected to people’s desire to experience a major holiday? In the case of Christmas, we were able to identify both a group of people who had less interest than average in experiencing Christmas and a group of people who had more interest than average in experiencing Christmas. The group we expected to have little desire to experience Christmas consisted of people who are likely to be Jewish. When we examined only people who had any of 106 Jewish surnames identified in previous research (such as Goldberg or Silverstein), the Christmas death deferral effect almost completely disappeared.

To identify people who were likely to look forward to Christmas more than the average American, we identified everyone in this population who had died as children. The very modest 3% effect for Christmas obtained for the entire population (shown in the graph above) became a much larger 30% effect for children. Taken together with other research in health psychology suggesting that people’s attitudes and expectations influence major health outcomes, these findings suggest that the basic human desire to be connected to other people (often called the need to belong) may play a powerful and pervasive role in human health and well-being, including in the timing of death. Eventually, everyone has a date with the grim reaper. But some people seem to find a way to push that date back a bit.

For Further Reading

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong; Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529.

Phillips, D. P., & Feldman, K. A. (1973). A dip in deaths before ceremonial occasions: Some new relationships between social integration and mortality. American Sociological Review, 38, 678–696.

Shimizu, M., & Pelham, B. W. (2008). Postponing a date with the grim reaper: Ceremonial events, the will to live, and mortality, Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 30, 36-45.

About the Authors

Mitsuru Shimizu is a social psychologist at Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville who studies eating, health, and self-evaluation. Brett Pelham is a social psychologist who studies gender, the self-concept, social inequality, and other social psychological issues. Brett is also an associate editor at Character and Context.