What essential qualities do you look for in a potential romantic partner? Perhaps you’re after an athlete, a movie nerd, or someone with a handlebar moustache. At the very least, you probably want to be with someone who is warm, kind, and treats other people well. And all things considered, the warmer and kinder your partner, the better…right?

Well, maybe not.

It’s true that we like kind, generous people and that we especially value these traits in our romantic partners. Most of us desire warm, loving relationships and naturally believe that such relationships are obtained by pairing up with warm, loving people.

However, there is another relevant factor that is far less obvious: How uniquely does your partner treat you compared to how he or she treats other people?

Although it makes sense that we are drawn to people who treat us well and treat others well too, our research shows that it is often the relative relationship between how they treat us versus how they treat others that matters most.

We find that people strongly desire their romantic partners to treat them uniquely. In our surveys, people consistently selected unique treatment as one of the most important qualities in selecting a partner—on par with honesty and trustworthiness.

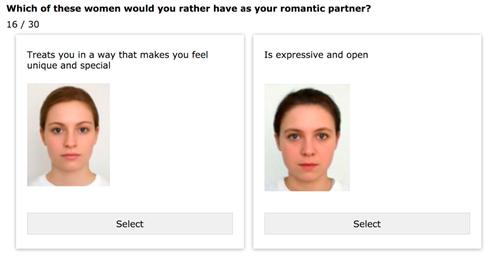

In a simulation study using photographs of human faces, people were more willing to have a relationship with a significantly less attractive partner who offered them unique treatment than a more attractive partner who exhibited some other trait, such as being athletic or highly educated. In the image below, you can see an example of our research materials that shows the type of questions people answered in our study.

Moreover, despite the fact that people generally want their romantic partners to treat others well, they nonetheless often prefer that their partner treat other people worse so that they themselves can be treated uniquely, even when it would be possible for their partner to treat them and other people equally.

Consider gift giving, for example. In one study, we showed people two laptop computer cases, one of which cost a dollar more but was significantly more durable and had a more attractive design. When we simply asked people which case their romantic partner should get for a coworker, almost everyone said the partner should pay an extra dollar to get their coworker the superior case.

However, if we first told people that their partner had previously bought the superior case for them, nearly half of our respondents said that their partner should get their coworker the inferior case. Even though the partner could have bought the superior case for both them and the co-worker, people preferred that their partner treat the co-worker worse than them.

Although this behavior may seem selfish, people were also willing to accept worse treatment for themselves, as long as it meant receiving unique treatment from their partner.

In one study, we showed people two different styles of Facebook posts—both wishing the recipient a happy birthday—and asked respondents to indicate which one they would prefer to receive. We then showed them a series of birthday posts and asked them to imagine that their real romantic partner had written these posts for friends and family members.

If the messages their partner wrote for other people were in the same style that the participant preferred, participants changed their mind—and chose to receive the message they liked less—over half the time! In other words, most people preferred to receive a unique message, even if it was in a style they didn’t love.

In another study with Snapchat users, people most preferred to receive—and were most likely to reply to—unique messages from their partner that were not also posted to their partner’s public “story.” However, people didn’t seem to care whether they got a non-unique message—that is, a message that was sent to them and also posted publicly for others to see—from their partner or didn’t get any messages from their partner at all!

Interestingly, the senders of these messages did not predict that their partners would respond this way. They incorrectly believed that their partner would prefer to receive some sort of message, even if it wasn’t unique. In reality, people felt that the non-unique treatment from a partner was on par with receiving nothing at all.

This misprediction is important because unique treatment relates to relationship satisfaction in the real world. When we surveyed couples at a museum event, we found that the more uniquely people felt their partner treated them compared to other people, the more satisfied they were with their relationship.

So, is the solution just to always treat your partner in a unique way? Well, not exactly. Although people consistently opted for unique positive treatment and would accept unique treatment that they didn’t prefer, they deeply disliked unique negative treatment.

Our final study showed that, if their partner typically used a certain term of endearment (such as “sweetie”) when communicating with friends and family members, most people wanted a unique name for themselves (such as “honey”). However, if their partner typically used a certain insult (like “idiot”) when communicating with or about others, most people wanted to be called the same thing rather than a unique term (like “moron”).

Clearly, the preference for unique treatment from romantic partners is nuanced and complex. But it’s important to understand because it impacts how people select, evaluate, and interact with their partners and how satisfied they feel with their relationships. So, what can you do?

We recommend openly communicating with your partner about both of your preferences surrounding unique treatment. It may be worthwhile to take stock of instances in your daily life where relative treatment is easily compared (such as in gift giving or on social media) and consider how your behavior may affect your partner.

If you discuss these behaviors, preferences, and feelings openly with your partner, you can work together to find compromises in your expectations of each other’s behavior and likely have a healthier, more satisfying relationship as a result. And if the conversation gets heated, don’t call your partner a moron—unless you call everyone else that too!

For Further Reading

Anik, L., & Hauser, R. (2020). One of a kind: The strong and complex preference for unique treatment from romantic partners. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 86, 103899. https://tinyurl.com/vnb93sd.

Lalin Anik is an Assistant Professor of Business Administration at the University of Virginia Darden School of Business.

Ryan Hauser is a doctoral student in marketing at the Yale School of Management.